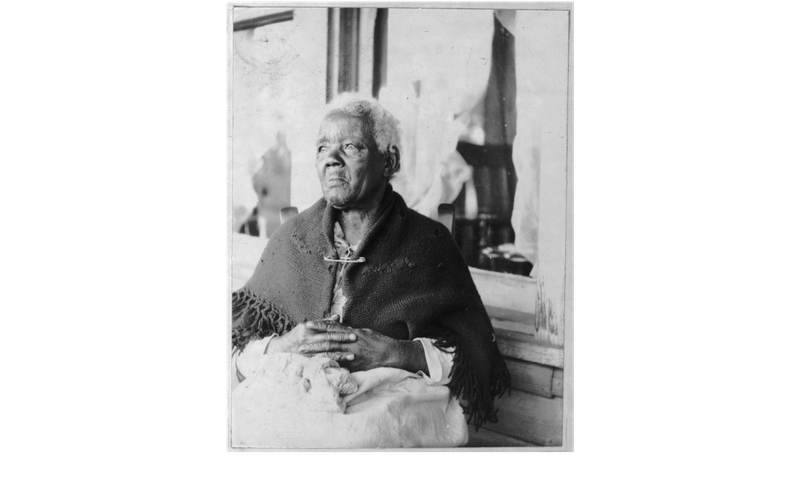

In observance of Black History Month we're sharing the history of a woman named Sarah Gudger, a woman born into slavery and who died free at the astonishing age of 121. Due to her age became quite famous in the Blue Ridge Mountains. This is her story.

Aunt Sarah

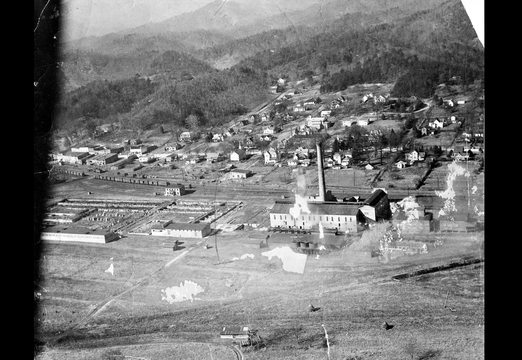

Sarah Gudger, known by all as “Aunt Sarah,” was born into slavery on Old Morganton Road near Old Fort in approximately 1816. Because birth records weren’t maintained for slaves in those days, scholars, journalists, and Sarah herself could only estimate her actual age using whatever records and memories are available. But the combined information from all of the available sources puts Sarah’s age at death at 121.

The best source of information is Sarah’s own life’s story, told in a 1937 interview with the Federal Writers Project, aimed at documenting and preserving the history of living slaves.

Nearly Five Decades A Slave

Sarah describes her difficult life as a child-slave living on the Andrew Hemphill Plantation near what today is Weaverville, NC. Her father, Smart Gudger, did not live with them and had taken the family name from his owner, Joe Gudger, who owned property in Oteen on the Swannanoa River. Unlike many slaves, Sarah was fortunate that her mother lived with her there for most of her childhood.

She worked outside from morning until late at night, chopping wood, carding wool and spinning it into fabric, hoeing corn, and working the fields, regardless of rain or snow. She recounted the backbreaking work, sleeping on rags, getting a small piece of cornbread with a dab of molasses to eat every day, and making their own medicine to care for their sick.

When Sarah’s owner Andy Hemphill died, she was willed to his son William whose property she remained until slaves were freed by Abraham Lincoln in 1863. While many slaves either followed their emancipators back up north or fled to other areas of the country, like Sarah’s brothers did when they relocated to California, Sarah saw no good in leaving everything she knew.

Sarah’s mother, Lucy McDaniel, carrying the surname of her most recent owner, died in 1862, just a few short years before she would have been emancipated.

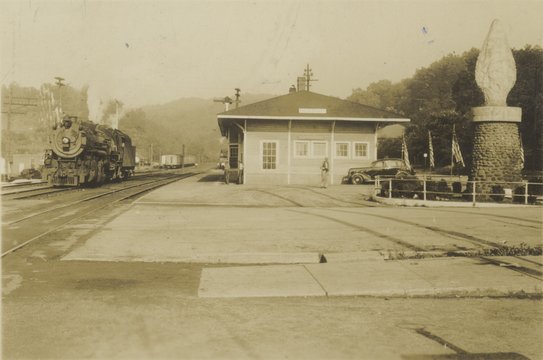

Within a year of being granted her freedom, Sarah moved in with her “Pappy” where he was living in freedom. He continued to work for his former ‘master in Swannanoa until he died in 1890 - 1891. She then moved in with her family in Buncombe County and became a local legend in Asheville, where she lived until she died in 1938.

Sarah's Legacy

Visitors can still catch glimpses into Sarah’s life. In 2015, Clayton Hensley, a builder by trade, noticed an abandoned cabin off Reems Creek Road in Weaverville. He says, “I thought, here was a piece of history that needs to remain on Reems Creek.” As it turns out, it is believed to have been built by John Robert Hemphill, family to Sarah and her mother Lucy’s original owners. Today it is a private residence, but the new owners did their best to maintain as much of the original cabin as possible, salvaging the timbers, parts of the tin roof, and even an old iron door key.

Additionally, the stairs in the restored Zebulon B. Vance Birthplace on Reems Creek were taken from the dilapidated Hemphill cabin. Zebulon Vance became the governor of North Carolina in 1862, and his birthplace is a popular historical site, especially popular for student field trips and history buffs. You are invited to take a tour of the site, including a visit inside a 1790s slave dwelling to hear their stories.

Just down the street from the two-story frame house in South Asheville where Sarah spent the remainder of her free life with family is what is believed to be Sarah’s final resting place.

The South Asheville Cemetery, the oldest public African-American cemetery in Western North Carolina, is actually home to 2000 graves. Of these, only 98 have gravestones, many of which are only identified with generalities, like the one marked “Mother.” Over the last few decades, volunteers, including a professor and his students at Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, have been in the process of reclaiming and preserving the cemetery. Hundreds of volunteers have worked to clear the forest from the site to preserve its historical significance.

You can read more about Sarah's life through this online exhibit from the Swannanoa Valley Museum and History Center.